Zak Amin teaches English as a Second Language and Kurdish language and culture at Moorhead High School and the Vista Education Center. (Photo/Nancy Hanson.)

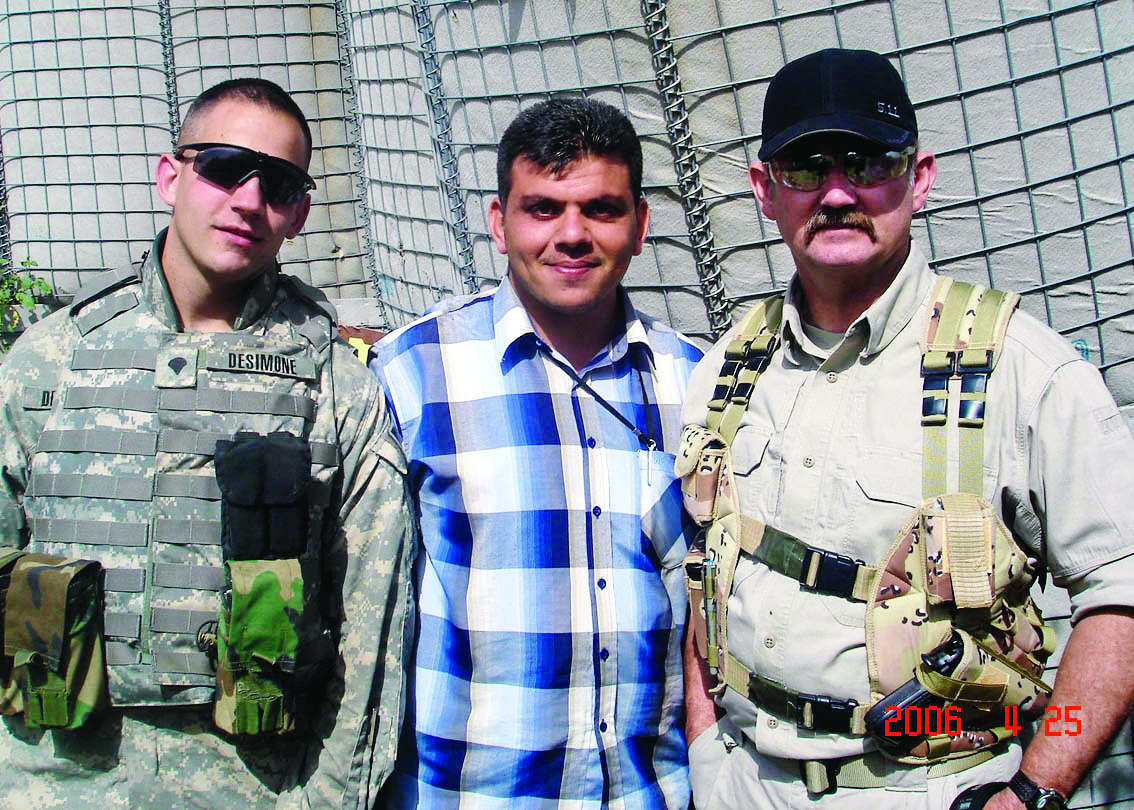

Translator Zak Amin stands between two U.S. police trainers during QRF (Quick Reaction Force) training in Erbil in the Kurdistan region of Iraq. (Photos/courtesy Zak Amin.)

Nancy Edmonds Hanson

For nearly a decade, Americans serving in the Middle East counted on Zakaria Amin to help them communicate with his Kurdish neighbors. Now, another 10 years later, he is helping young Kurdish-Americans communicate, too … with their elders in the language they left behind.

Zak teaches ESL – English as a second language – at Moorhead High School. His students include those from a variety of backgrounds beyond the land from which he and his family emigrated in 2015: Moorhead students come from homes where 42 languages are spoken.

But, thanks to his work with KADO, the Kurdish American Development Association, he also turns that language paradigm on its head. Held after the school day ends, he leads a class in the Kurdish dialect of Sorani at the Vista Education Center. The instruction helps English-speaking children bridge the communication gap with their parents who still speak their native tongue. “I want to help the parents become more Americanized,” he says, “but also help the kids develop a sense of pride in their Kurdish heritage.”

Zak earned a bachelor’s degree in English language and literature at Salahadin University in his home town of Ervil, the capital of Iraqi Kurdistan. He was a reporter for Kurdistan’s only English-language newspaper and taught middle school for several years before signing up, in 2006, to translate for the Americans.

He worked as a translator under several private companies contracting with American interests. They included the Civilian Police Assistance Training Team, which worked with the U.S.-led coalition to rebuild the Iraqi police, and the International Bureau of Narcotics and Law Enforcement. “We traveled to Kirkuk, to Mosul and very dangerous places,” he remembers. “The terrorists were bombing us. I’ve been shot. There were explosions very close,” he remembers.

After the U.S. pulled out of Iraq, Zak applied for the Special Immigrant Visa, available to people who worked for the U.S. military or under Chief of Mission authority in Iraq. He and his wife Rozhgar (Rose) arrived in Fargo-Moorhead in 2015 with the first of their three sons.

“My wife was not happy,” he admits. “She has a very large family there, and we were so attached to them.” But he encouraged her to leave Kurdistan, where the terrorists considered men like him traitors, targeted for murder. “I said, ‘Let’s try it and see what it’s like,’” he remembers.

Settling in their new home wasn’t easy. Despite his degree in English and experience as a translator, Zak says finding a job was very difficult. “My degree didn’t count for teaching here,” he says. “I interviewed 50 or 60 jobs with no luck.” Some seemed promising, but never called back. In the meantime, he used his three languages (Kurdish, Arab and English) do translate in medical and other situation and continued freelancing for the Kurdish newspaper.

But he could find no full-time work. So he went back to school, first earning an associate degree in accounting at M State. He went on to enroll at Minnesota State University, where he earned a master’s in teaching English as a second language.

Finally, Zak was hired as an administrative assistant in Moorhead’s Community Education program in 2018. He was, he notes, the only non-U.S. native and only male working for the department. “Lauri Winterfeldt (the director, who’s since retired) hired me. She was my angel,” he smiles. “She is like my American mom.”

He went on to other jobs in the Moorhead schools, including working as a paraprofessional at Horizon East Middle School and as a liaison with the district’s Kurdish and Arabic families, the largest non-English speaking population in the district.

Then at last he was hired as a teacher. Today Zak is in his third year as an ESL instructor at Moorhead High. Along with other classes, he teaches a Kurdish class for students who are born or raised here. “My aim is to educate them to know about and keep their Kurdish identity,” he says. The class includes the geography, history, music and language of the land their parents left behind. Since advocates his students speaking English by day in school and the larger community, but using the Kurdish language at home with their parents. “It helps create better, deeper relations between their family members and, in turn, between their parents and the school.”

The Kurdish language and culture class has been so successful that Education Minnesota named him the state’s Human Rights Award. “The parents were speaking Kurdish, but the children were speaking English. They understood each other, but there was a big gap,” he explained to the teachers group.

Zak and Rose became American citizens in 2020. Even now, however, they do not feel completely accustomed to their home. “I’m still in the process of getting adapted,” Zak says, “even though two of our boys were born here, they go to school here, and I work here.

“A couple years ago, I went back to Ervil. I felt like a stranger … so many social changes. Those I knew as kids are old now, and some of the old have died. It was kind of like another planet – not another country, another planet. My personal connections are gone. There is a lack of jobs; it is ‘who you know’ to find one.”

Zak is in the middle of writing his memoirs, telling the stories that have made him the man he is. One of those chapters, no doubt, will tell of his first run for public office, his campaign this fall for a seat on the Moorhead City Council. He came in second to incumbent Sebastian McDougall.

He may well become a candidate again. In the meantime, he says he learned a good deal about the community by knocking on doors and talking with the constituents who answered. “I didn’t make it, but I got a lot of votes. A lot of people supported me. I won a lot of endorsements. And a lot of people are telling me you should run again.”

He plans to continue his work bridging the cultural and language gap, both at the high school and through his volunteer work with KADO.

Considering his life and the unexpected turns that it has taken, he says he is comfortable with what he has accomplished so far, but hopes to encourage more mutual understanding – between Kurdish-American children and their parents, between families and this community — in years to come. “I would not exchange what I have here for going back to where I grew up, where I once lived,” he says. “That life is gone.”