Clay County Histories

Markus Krueger | Program Director HCSCC

At a recent family holiday gathering, I looked on with interest as my nephew Mark, a 14-year-old obsessed with old things, tell his cousin Ada, a 3rd grader who loves all things scientific, about a piece of 40-year-old antiquated technology in his hands. Ada was unfamiliar with the plastic object. It was about the size of her parents’ credit cards but thicker and containing a black ribbon wound between two gears.

“Do you know what this is?” asked Mark.

“No…” Ada replied with curiosity.

“It’s called a cassette,” replied the family’s eldest cousin. “You use it to play music. Guess how many songs it has on it?”

Ada was unsure. “A hundred?”

“Nope. More like ten.” Ada’s face displayed surprise and confusion. “But you didn’t have to listen to any ads.”

I chose to shoo away any thoughts of self-pity about how things I once bought new are rapidly becoming historical artifacts that inspire wonder among my nieces and nephews, and instead I focused on how differently we experience music through the generations.

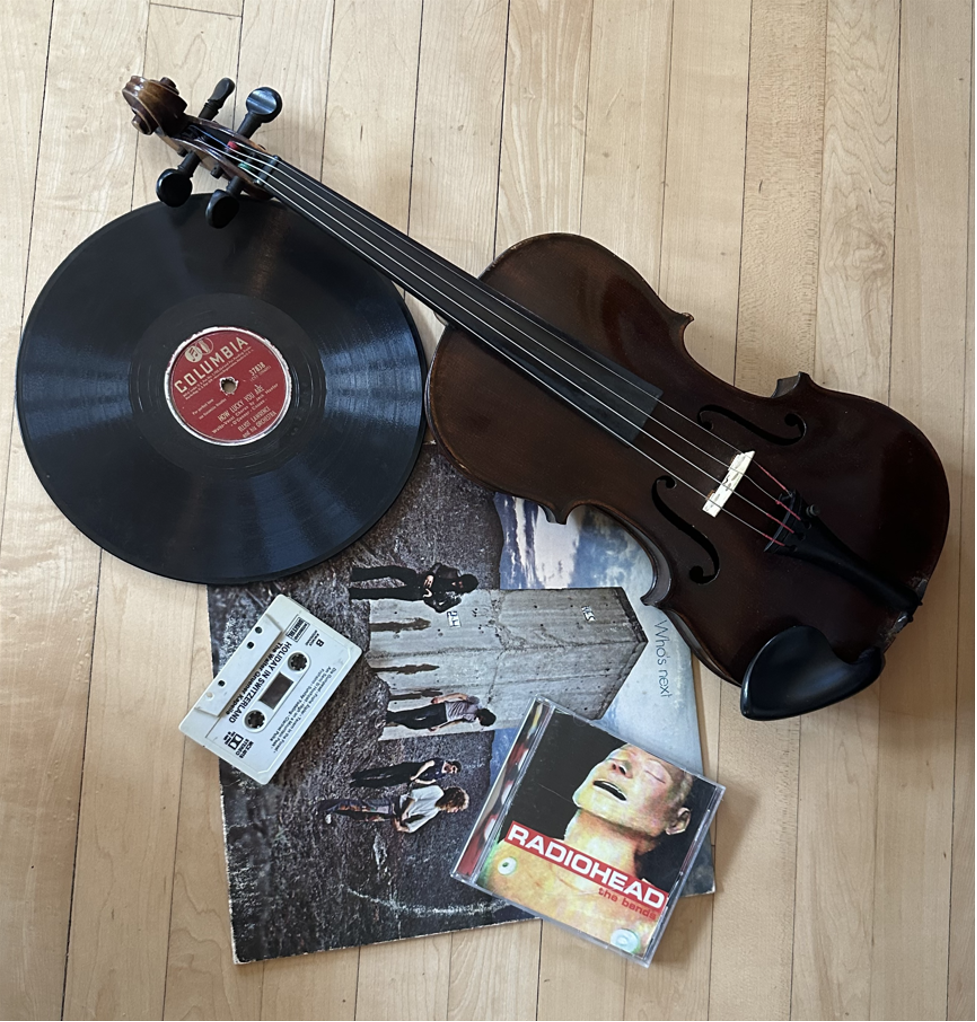

That night I introduced Mark to some of my favorite musicians. I called out songs and he summoned each one up on his phone instantaneously for free, although he had to listen to commercials before the song played. I gained my musical knowledge through 20 years of trail-and-error purchases, mostly of $15 discs of plastic containing a dozen songs that I listened to on a CD player, but I also owned machines that played my records and cassettes. To hear music at home in the 1800s, our ancestors had to become musicians and purchase violins, banjos, pianos and sheet music. Kings of old had to pay musicians to hang out around their palaces to hear their favorite songs. Today music is piped in digitally by speakers in the ceilings of most places we go – you hear it everywhere, but it is physically nowhere.

The next evening, I was reading the book Enlightenment Now by Steven Pinker. Pinker believes that in affluent countries like the USA, we may have already reached “peak stuff.” Future generations, he says, will own fewer physical objects than we do now. Looking at all the toys and gadgets that litter the homes of my nieces and nephews, that is hard to believe.

But Pinker may have a point. Apart from the antiquarian Mark, these kids won’t buy CDs or vinyl records. In my brother’s well-read family, many if not most of the kids’ bedtime stories, as well as Dad’s sci-fi novels, are experienced through digital audio rather than physical books made of paper. “On Demand” entertainment channels mean much less plastic and metal is bound up in DVDs and the specialized machines needed to play them. Most college students today take notes digitally rather than with pen and paper. My pockets typically contain nary a coin nor bill. Our smart phones replace the need to manufacture separate physical calculators, compasses, watches, pedometers, road maps, tickets to concerts or sporting events, photo albums, books of Sudoku puzzles…and oh, yeah, they’re phones, too!

I wonder, in 100 years, what physical artifacts will Mark and Ada’s generation add to the historical collection of our museum? And what will I get them for Christmas?