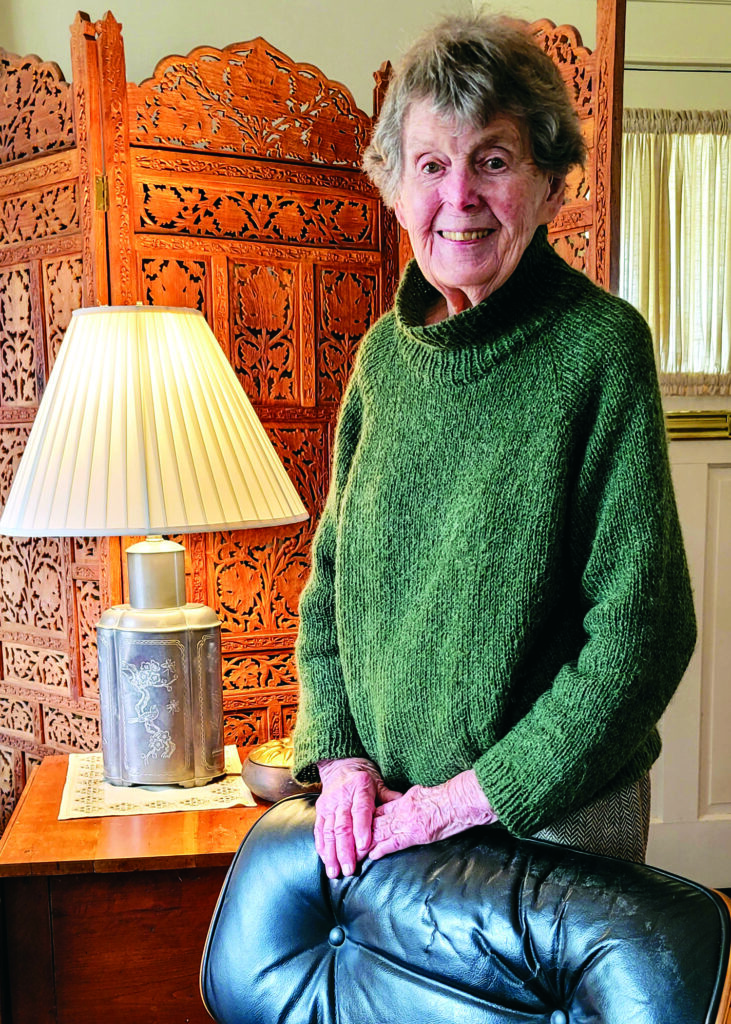

Retired professor Barbara Glasrud still lives in the house she and her late husband Clarence (“Soc”) bought in 1952. (Photo/Nancy Hanson)

Nancy Edmonds Hanson

Some artists work with canvas and paints, others with metal or stone. Barbara Glasrud’s artistry soars beyond the everyday materials of visual art: Her talent is the gift of opening young eyes to the masterpieces of the ages … enthusiasm, curiosity and vast knowledge of the history of art.

“That’s the part of teaching that I loved best,” the retired professor reflects. “I liked opening students’ eyes to art. It was a privilege, both to teach in the classroom and to take them to Europe during May Seminars to experience the same wonderful art face to face.

“It’s funny,” she adds. “The one thing I was sure of in college [at Carleton, where she majored in art and minored in Greek] was that I did not want to teach.” Her husband, Clarence Glasrud, better known as “Soc,” was destined to be the teacher, she believed, while she stayed at home with their only son, Charles. But after being approached again and again to become a guest lecturer at Concordia College within an easy walk of their home, she finally agreed to try it.

That was 1961. She started as a part-time lecturer without even a desk to call her own. In 1976, she became a full-time member of the faculty … and was named chair of the art department. She developed four art history courses and taught them all – a role she relished with passion until her retirement in 1992.

Born in Lake City in southern Minnesota, Barbara met her future husband as a freshman when he taught English at her high school. She went on to study museum curatorship at Carleton and work at the Minneapolis Museum of Art before going on to Bryn Mawr College, where she completed a master’s in Oriental art history in 1947.

Meanwhile, she accepted a marriage proposal from her former English teacher, now home after serving in the Army Air Corps in Europe. The Glasruds were married and moved to Moorhead in 1948, where her husband taught briefly at Moorhead State College. “We couldn’t find anywhere to rent,” she said, remembering Moorhead in its great post-war boom. “Finally we found a place in the barracks that had been built south of the campus to house professors and students back from the war. What I mostly remember of my first impression? It was so hot, so windy. And hay fever!”

The couple headed to Harvard two years later, where Clarence earned his doctorate in English. “I got the best job I could possibly have,” she reminisces, “as assistant curator at Harvard’s Fogg Museum in my specialty, Chinese art.”

The Glasruds returned to Moorhead in 1952, moving into the house just north of the Concordia campus where she continues to live. There they raised their son Charles, now a judge in the 8th Judicial District in Morris, Minnesota. Charlie, as his mother calls him, shared his parents’ travels, coming along as they spent two sabbaticals in Europe. For the first, when he was 8, the family shipped their car to Scandinavia, then spent the next 12 months traveling the continent from top to bottom. He was 13 during their second six-month trip; this time, the Glasruds purchased a sporty red Fiat in Italy, ferried it to Greece, then eventually drove it back and shipped it home to Moorhead.

Clarence and Barbara’s lifelong love of travel took them around the world, not only throughout Europe but to China, Japan and India. They were among the first Americans to visit China after the demise of Mao Tse Tung, then returned a few years later to see a nation in the midst of rapid change.

Along the way, Barbara shared her passion for art with the community beyond the campus. One memorable moment occurred 60 years ago when – as a member of what was then called the Junior Service League – she helped organize one of the area’s first invitational art shows. “We received entries from all over the region, then wondered, ‘Now, what are we going to do with these?’” she remembers. They secured space for their exhibition in the lobby of the Gardner Hotel. “But how were we going to hang them? I asked Cy Running [Concordia art instructor] how to find help, and he thought of a couple brothers who he believed would help us out.”

The brothers: Orland and James O’Rourke. “They did a beautiful job,” Barbara recalls. “They enjoyed it so much that they went out and rented a small vacant space – a pizza parlor, I think – on the Moorhead end of the Main Avenue bridge, and they opened their own gallery.” Their enterprise soon outgrew its space and moved to the Martinson house on Fourth Street South, becoming the Rourke Gallery. Jim continued to operate it until his death, while brother Orland spent his career teaching art at Concordia.

That’s only one of the countless connections Barbara has forged over the years. Another links her to Peter Schultz, the energetic art lover and idea generator who’s behind the new Rourke lectureship in her honor, the Barbara Crawford Glasrud Endowed Lectureship on the History of Art. He himself delivered the inaugural lecture Monday, a talk on the artist Pieter Bruegel and his famous painting “The Tower of Babel.”

“During my last year of teaching, I had one student who shouldn’t really have been in my class. It was at the upperclass level, and he was a freshman. But he was doing well, so I let him stay,” Barbara remembers.

The student, Schultz, became a good friend. After the death of her husband in 2008, the two came up with the idea of “hanging out in northern Italy,” as he describes it. The travel group he helped put together became the genesis of one of the highlights of Barbara’s weeks today – the regulars of her “Malbec Mondays,” when they gather in her living room to enjoy a glass of fine wine and good conversation, sometimes sharing the company of a coterie of visiting kittens.

It was members of that group who came up with the idea of honoring their centenarian hostess with the annual art lectureship they kicked off Monday. Schultz cites her longtime neighbors Ira and Ken Bailey, Gary and Melody Larson, Jonathan and Cady Rutter, and Barbara’s son Charlie as the guiding committee that has set out to fund the endowment. Their goal is $90,000 to bring noted art historians to Moorhead in perpetuity.

Schultz recalls Barbara’s grace as a teacher: “She was an elegant, graceful and inspiring educator,” he observes. “I didn’t have the words to describe it at that time, but now I’d call what she generated in me a kind of intellectual euphoria.

“I was all set to join the Army and do engineering. I got into her class pretty much at random. It completely changed my life.”