Clay County Histories

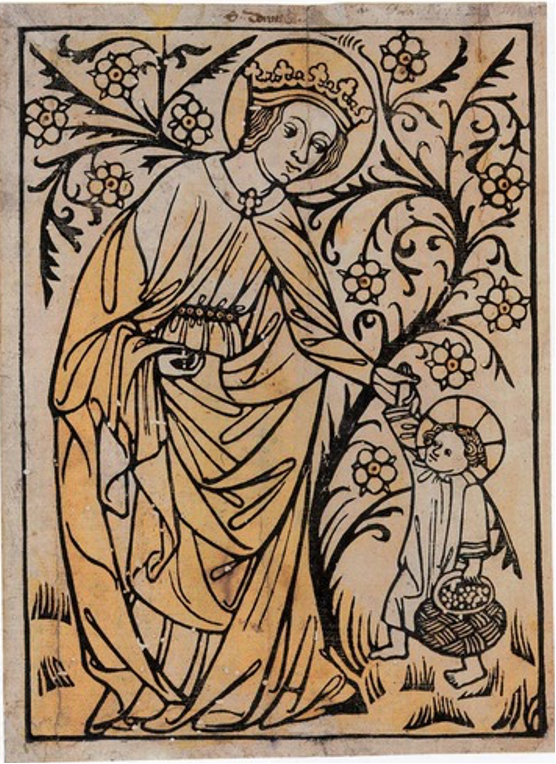

“St. Dorothy and the Christ Child,” German woodcut print, 1410-20.

Markus Krueger | Program Director HCSCC

Printmaking is one of the newest major art mediums. Cavemen and Cavewomen made paintings and sculptures dozens of thousands of years ago. The first examples of prints in Europe appear in the early 1400s. It is a simple artform in concept: carve a design into a plank of wood, smear it with ink, and press a piece of paper to it. Why did it take us so long to think of it? There was a missing ingredient.

Carving wood was nothing new. Ink had been around for centuries. Did we need to invent the printing press first? That’s a good guess, but the first prints did not use presses. The missing ingredient was paper.

Paper is a relatively recent invention. The first writers, the Sumerians in what is now Iraq, wrote everything from epic stories to business inventories by pressing wooden styluses into wet clay, which would be sun dried or fired to preserve the document. The Romans wrote on scrolls made from the processed bark of the papyrus plant, a practice that they learned from the ancient Egyptians. Ancient Chinese scribes wrote on bamboo strips that were tied together. Medieval monks wrote on vellum, an expensive processed calf skin.

About 2000 years ago, Chinese craftsmen came up with paper as we know it by soaking wood pulp and old rags in vats of water, dipping a mesh screen into the soupy decomposing muck, and letting that muck dry on the screen to create a sheet of paper. The beauty of the papermaking process is that it recycled garbage (sawdust and worn-out clothes) into something very useful. That knowledge spread to Europe about 1000 years ago, but it wasn’t until about 1400 that European papermakers were cranking out enough paper to make it affordable and commonly available. Only then was the artform of printmaking possible.

Painters were employed to draw an image. A different craftsman glued that drawing to a plank of wood and used chisels and knives to cut out the design. Someone else covered the carved plank of wood with ink and pressed a piece of paper to it. Finally, regular people could afford to hang art on their wall.

Cheap paper was also the missing ingredient for something far more important: widespread literacy. One of the reasons that very few people could read and write in the Medieval and Ancient times was the stuff we were writing on – papyrus from Egypt or processed calf skin – was so expensive and rare that most people couldn’t afford to own any of it. Why learn to read if you’ll never own a book? In the 1450s, Johannes Guttenberg used cheap paper for his new process of making lots of copies of books all at once with movable type and a printing press. At the beginning of the 1400s, each book was laboriously copied by hand on expensive calfskin. By the end of the century, affordable books were printed thousands at a time on inexpensive paper. Paper was the missing ingredient that literally put education within peoples’ grasp by putting affordable books in peoples’ hands.