Nancy Edmonds Hanson

A business of your own – it’s the dream that’s impelled men and women to launch companies large and small. Running it becomes a life style, defined by long hours, hard work and day-to-day challenges. But the greatest challenge of all may still lie ahead: Placing the keys in a new owner’s hands and walking away.

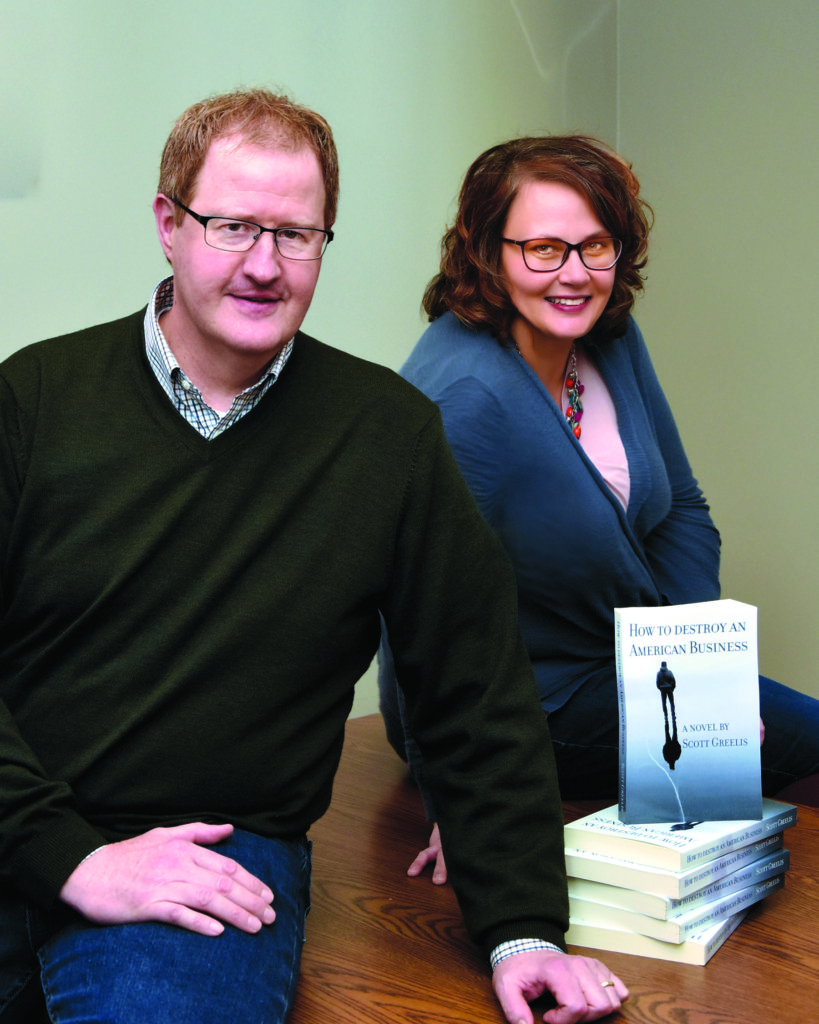

That’s where Scott Greelis of Moorhead comes in. Until five years ago, he divided his career as industrial engineer between stints as employee and as entrepreneur. Now he devotes himself, full time, to helping small business owners get the most from their enterprise now … with an eye to shaping them to appeal to a willing buyer.

“Small business owners tend to be jacks of all trades,” he observes. “When something needs to get done, they just do it themselves, whether they’re good at it or not. That can work as the years go by But when they are finally looking forward to retirement, it’s a different story. They need to have processes, revenue and strategies in place so that the business that’s been their own lifestyle can be carried on by someone else. If nobody else can run it but the owner wants out, you’re going to have a problem.”

A big part of Greelis’s consulting business, Lion’s Way, is focused on helping businessmen and -women prepare for that moment – the time they will place their “babies,” the work of a lifetime, into new hands and get on with the next chapter of their lives.

He and his wife Deb, who works alongside him, know that wrenching process firsthand. Both graduates of the University of North Dakota, he used his engineering degree to design snowmobiles for Arctic Cat and control systems for tractor harnesses for Phoenix International, while she worked for Norwest Bank through its purchase by Wells Fargo. Then, nearly 20 years ago, Scott left corporate positions behind to pursue an idea of his own – using European technology to manufacture durable, lightweight ceiling and floor liners for industrial equipment, using hemp fiber imported from Bangladesh. His new Fargo-based company, Composite America, sold the idea to Bobcat and John Deere. “Everything we had was tied up in that project,” he says. “The outlook was great.”

Then came the Great Recession of 2008. In 60 days, Composite America lost 80 percent of its sales. Everything they had was tied up in the research and development of those products. “We had to lay off our employees,” he remembers. “We had to do it all just to keep the doors open.” But two years later, when the recovery revived his industrial clients’ plans, his hemp-based liners and panels were part of the specs for their new models, and they could carry on.

Greelis sold the company in 2010. The purchase agreement with Melet Plastics (which continues to operate the company at its original location in Fargo) included his staying on for several years to run it. It was wrenching to linger, not as the founder and boss, but as the manager. “When you’ve started from scratch – literally chalk drawings on a bare floor – and built a business, it’s your baby. Your sweat, tears and sacrifices are there,” he reflects now. “It’s tough. I wasn’t going to hang around and be a cancer, so I left.”

After three years managing a steel company with seven sites in five states and 500 employees, he and Deb were weighing their options. “I had offers from southeast of here, but our family has lived in Moorhead for 20 years. We love it here, and we weren’t going to uproot our kids and move,” he says. (The couple has two sons, now 17 and 13, and an 11-year-old daughter.) “Should we go into manufacturing again? Look at a franchise? Deb asked, ‘What do you really love?’ That shifted our thinking.”

They have worked together in Lion’s Way – a team approach that’s a particular asset working with family-owned businesses in which both spouses are involved. They work with 10 to 12 clients at a time, most with annual sales of $3 to $10 million – primarily in Minnesota, but now following some past customers into Arizona, Texas and Florida markets.

Their engagements fall into three increasing complex categories. “Some business owners just need a tune-up,” Scott explains. “It’s not always about increasing sales. Some are seeing their sales go up but their profits going down. We take a look at their internal processes.” That leads into the second category, diagnosing problems on the bottom line. “It could mean jump-starting your sales when you’re overwhelmed and out of ideas,” he says. “The goal is finding ways to build sustainable profits.”

The third category is perhaps the one closest to his heart: Helping owners figuring out how to get their businesses sold. “I am not a broker or a glorified real estate salesman,” he emphasizes. “I help them focus on building value and putting the pieces in place that will appeal to a willing buyer.”

That often means the owner, accustomed to doing it all himself, needs to consciously hand off tasks to staff who can offer continuity when he’s gone. “There are two kinds of buyers: the older buyer who wants someone else to run it and has the money to invest, and the younger one with ambition but no money,” Greelis explains.

Then, too, there’s the third dynamic in the transfer of ownership. That’s the employees, whom he calls the bridge between seller and buyer. “They’re the business’s biggest asset. They carry all the tribal knowledge of how it works – the customers, the suppliers, the processes. If the contrast between the way the company has been run and the way the new owner runs it is too drastic, they tend to leave real fast. Too much change, without managing it carefully, can be a recipe for disaster.”

Those challenges can be even greater when the founder and his prospective buyer are two generations of the same family. “Generations have a huge gap in values. It’s certainly true of Boomers and Millennials, but it’s always been a fact of life for family businesses,” he reflects. “The older generation that built it places great value on long hours, hard work and sacrificing for the future. Their children are looking for fast results and maximun profits and place great faith on technology. Conflict is inevitable.”

Like all of the choices that contribute to business success – or not – intergenerational transfer can work out well, especially with clear communication and thorough preparation. But that outcome isn’t inevitable. It’s a dilemma Scott explores in his newly published book, “How to Destroy an American Business,” a fictional parable depicting the far-reaching effects of family dynamics and decisions both good and bad in the fortunes of a promising business venture. The novel is available from Amazon as well as Lion’s Way.

“Personally, I don’t like mixing family and business,” Greelis says. “I suppose at one time I had some romantic idea about passing my business on to my kids, about making it their legacy. Knowing what I know now, I’d have to think long and hard and lay a huge amount of groundwork before I’d want to try it.”