Nancy Edmonds Hanson

hansonnanc@gmail.com

Neil Braasch calls it “Black Monday” – the first weekday after Minnesota’s deer-hunting opener.

A steady stream of pickups and 4x4s pulled into the alley behind his home on the corner of Center Avenue and First Street in Dilworth. Each carried a happy hunter, who entered the Gourmet Game Processing shop where his garage used to be – a big grin on his face and arms full of fresh venison after a successful weekend hunt.

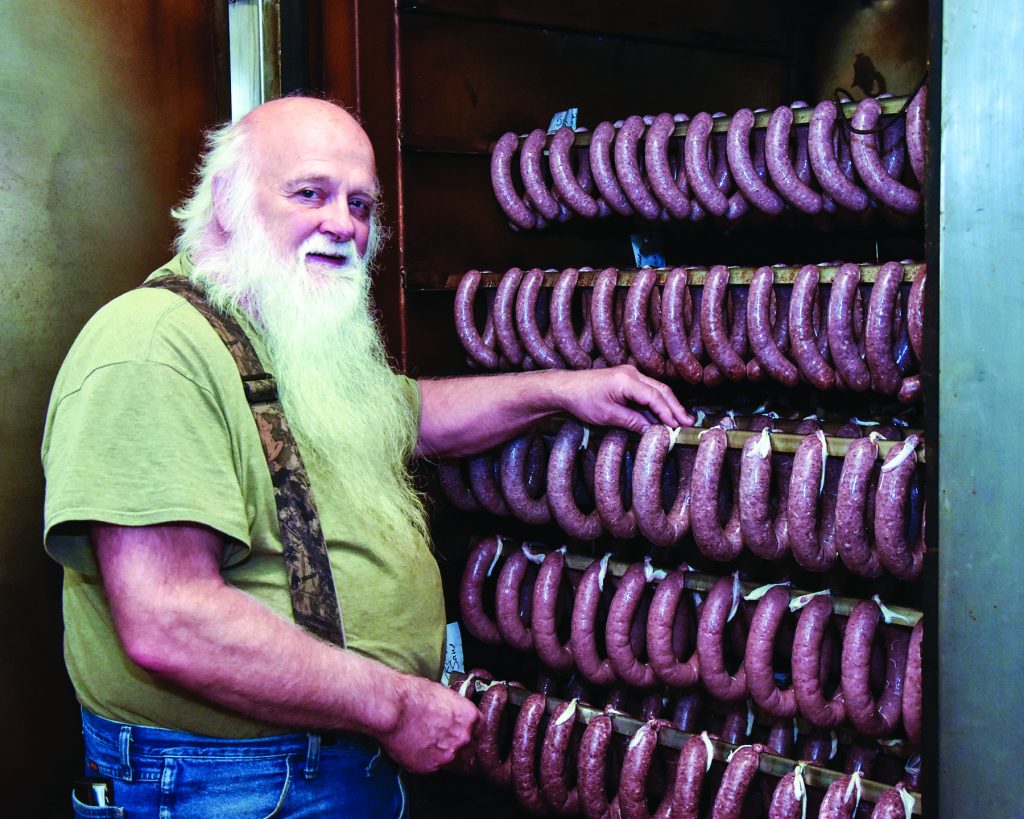

“And so it begins,” says Braasch, the -white-bearded meat cutter known far and wide for his sausage-making genius. “From now until the end of April, there’ll be no rest for the wicked.” He grins: “I guess I’m the wicked.”

From long before dawn to well after dusk, Braasch’s shop and seven or eight employees – among them wife Janet and son David – will be hard at work cutting that deer meat, grinding it, seasoning it, stuffing it into casings and smoking it overnight to create the exact blend of flavors each customer has in mind. When the onslaught overwhelms what can be processed the same day, boxes of the meat carefully labeled with their owners’ identification will begin to fill up the huge walk-in freezer. When even those floor-to-ceiling shelves are full, the Gourmet Game crew will advise owners to freeze it at home until shelf space opens up a few weeks later.

That freezer will fill, top to bottom, with venison at least three times over between now and when the crew catches up next spring. By that time, Gourmet Game will have produced more than 100,000 pounds of sausage – the product of at least 1,700 head of deer.

“You could say that meat-cutting is in my blood,” the Detroit Lakes native says. From the time his father, Lester Braasch, bought the Lake Floyd Locker Plant north of his hometown when Neil was 14, he has spent his days breaking down carcasses and turning them into tasty meals. “When I turned 16, he handed over his guns and knives and keys to the truck, and that became my part of the operation,” the 68-year-old meat cutter recounts. “I learned the basics of how to butcher critters on farms – how to shoot, where to stick the knife in, how to lift them on a hoist. By the time they went into the trailer, they were all washed and quartered for Dad to break down.

“But in 55 years in this business, I’ve got to say I far, far surpassed him,” he adds. “After this long in the business, if you can walk away stupid, you really are.”

After his father retired, he sold their smokehouse and their top-secret recipe for ring sausage to Milt Oberg, who had a locker plant in Georgetown. “I guess I was part of the deal,” Neil reports. He worked for Oberg for years, then after he too retired, went on to cut meat for Piggly Wiggly. Then he moved to Quality Beef and Seafood in West Fargo, where he learned to bone choice cattle. “I could do two to two and one-half per hour,” he recalls, “in my belly guard and mesh gloves, with about six knives and a boning hook.”

After cutting his arm badly on the job, he took a six-month hiatus. “But it’s in my blood to cut meat,” Neil asserts. After recovering, he learned Quality Beef didn’t have an opening. But the company had bought the federally inspected Fargo Packing sausage plant in the meantime. That’s where he went back to work, soon rising to plant supervisor.

“I took care of all the recipes for Fargo Packing for 20 years, including all the government paperwork,” he says. That included figuring certain ingredients in parts per million, as required by federal law. He still uses that format in his own shop, along with precisely documented procedures for every process and every product.

Gourmet Game Processing began as a side business he and Janet pursued in a 10 by 10-foot addition to their garage. His deer sausage quickly became legendary, drawing growing numbers of hunters every season. Neil built on to create the 24 by 56-foot shop they now occupy. (“My car sits outside,” he points out needlessly.) The shop has long since become a full-time enterprise. From now until the end of April, the telephone rings almost continually throughout every day.

Inside, along with the equipment and space required for making sausage, the Braasches have meat counters full of protein to sell to the public. Much of it centers on his endless array of top-secret sausage recipes, now numbering nearly 50, and his jerkies and smoked meats. He also carried the full range of domestic beef and pork cuts, selling both retail and to commercial establishments. He rarely breaks down cattle and hogs, though. “I buy what I need from Quality Boneless,” he confesses. “I know what’s best to order.”

Yet it’s his sausage that’s earned him a reputation throughout the tri-state area and beyond. The great bulk of it is deer, with each batch seasoned and ground to the specific tastes of the hunter who brought it in. “I don’t combine it for 300-pound batches. Everyone gets what he shot,” he notes. Beyond deer, though, he applies his skills to whatever customers bring in: Elk, antelope, buffalo, kudu (from game farms on the Texas border or, for that matter, Africa), emu, mountain lion, raccoon … “if they bring it in, I’ll make it.”

Though deer hunters are his bread and butter, their passion is beyond Neil’s reach … for now. Instead, he hunts bear, generally in the Lake Itasca neighborhood. “Bear season starts and ends before deer get going and we get busy,” he points out. “I prefer the meat, myself. It has less of that wild taste than deer. The important thing is it needs to be chilled, and fast, especially since the weather is generally warmer. Otherwise, it starts souring on you.”

Neil and Janet are looking toward retirement, probably after she passes a significant birthday in March. They plan to sell the business to son David. Neil has filled meticulous notebooks with all the details he’ll need to get a running start. “And if he runs into trouble,” he says, “we’re just 10 steps away.”

His knees have gone bad after 55 years standing, day after day, on concrete. “When I get them fixed, I want them to last awhile,” the meat cutter asserts. “We want to have some time to sit back and enjoy life.”

And what, exactly, is on Neil’s bucket list? “Wel-l-l,” the Gourmet Game Processing veteran suggests, “… I just might get in a little deer hunting.”