Clay County Histories

Markus Krueger | Program Director HCSCC

Every year, our museum teams up with Fargo-Moorhead-West Fargo’s public and academic libraries for One Book One Community, where we pick a book for a community read and do events on the themes of that book. This year’s book is The River We Remember by William Kent Krueger. One of the themes is veterans dealing with Post Traumatic Stress Disorder.

As part of the programming for this book, the Moorhead, Fargo and West Fargo Public Libraries, the libraries at Concordia, MSUM and NDSU, and the Hjemkomst Center will display masks made by local veterans at the Fargo VA as art therapy to work through trauma. Painting and gluing things onto a mask allows veterans a way to show things they may not have words for. Go see them.

Eddie Emberg was my grandma’s beloved little brother. This 17-year-old red-headed Minnesota boy from a railroad family enlisted in the Marine Corps on the day the Korean War started. He spent a year as a machine gunner in that horrific war that we so rarely mention. My father, an army veteran, has spent a lot of time gathering government documents and family stories to flesh out the life of his Uncle Eddie.

Eddie was taken off the line twice for medical reasons, but the details were lost in a government document fire in 1973, and everybody who knows what happened is dead now. Dad’s older brother Ray was told that the Marine feeding ammo to Eddie’s machine gun was shot through the head and that bullet went into Eddie’s face. Dad never heard that story, but it explains Eddie’s facial scar and false teeth. Dad recalls at Christmas about 1960, Uncle Eddie was scratching his leg and, when it started to bleed, he dug out a piece of shrapnel.

Eddie came home to Minnesota in 1953. He was addicted to morphine. After some bad months, his parents sent Eddie to his older brother Truman in Alaska. Truman was a veteran of the Alaska Scouts in World War II, so he knew a thing or two about what his little brother was going through. When Eddie returned to Minnesota, his morphine addiction was replaced by alcohol.

His psychological wounds never healed. He drank a lot, and sometimes stories would flow out late at night when he visited his sister’s house on holidays. Before the Chinese or North Korean armies attacked, they would force their civilians – men, women, and children – to run ahead of them into the American machine guns. They absorbed ammunition and their dead bodies provided cover for the attacking soldiers behind them. Eddie was forced to gun them down, the bodies piling so high he had to relocate his machine gun position.

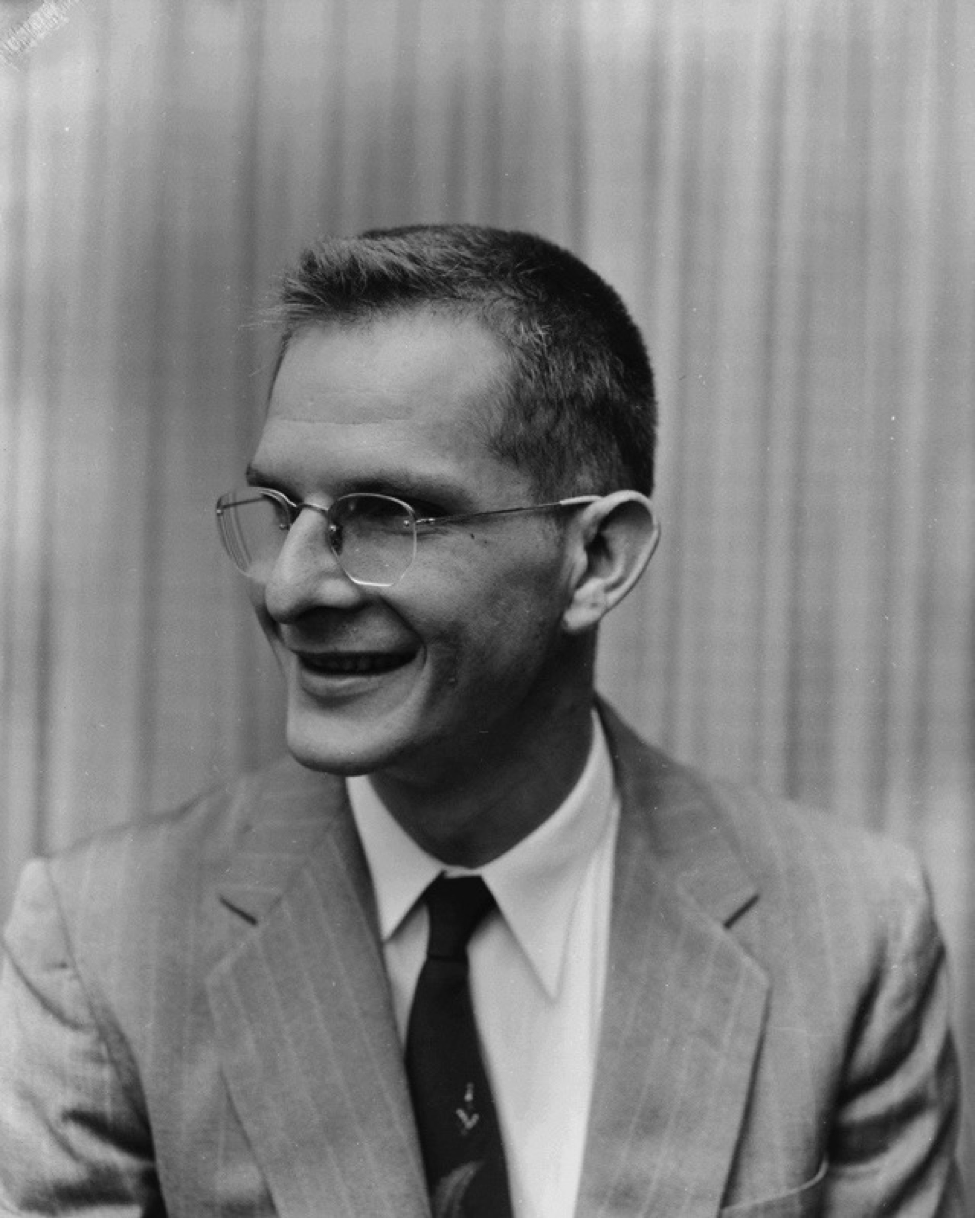

I could relate other stories of lasting trauma, but I could tell stories of good times, too, like how he would play his opera records over the loudspeaker at the Great Northern Railroad yard, or when he was elected to public office. He died in a house fire before I was born, but I still grew up with my Uncle Eddie. My grandma spoke about him all the time. She said I looked just like him. I’ve had a lifelong fascination with military history, but the stories my grandma and my dad told me about Uncle Eddie inoculated me against any glorification of war. I hate war. My interest stems, I think, from a feeling of responsibility. We ask a few of us to do such horrific things for the rest of us. I feel a responsibility to listen to them and remember them.