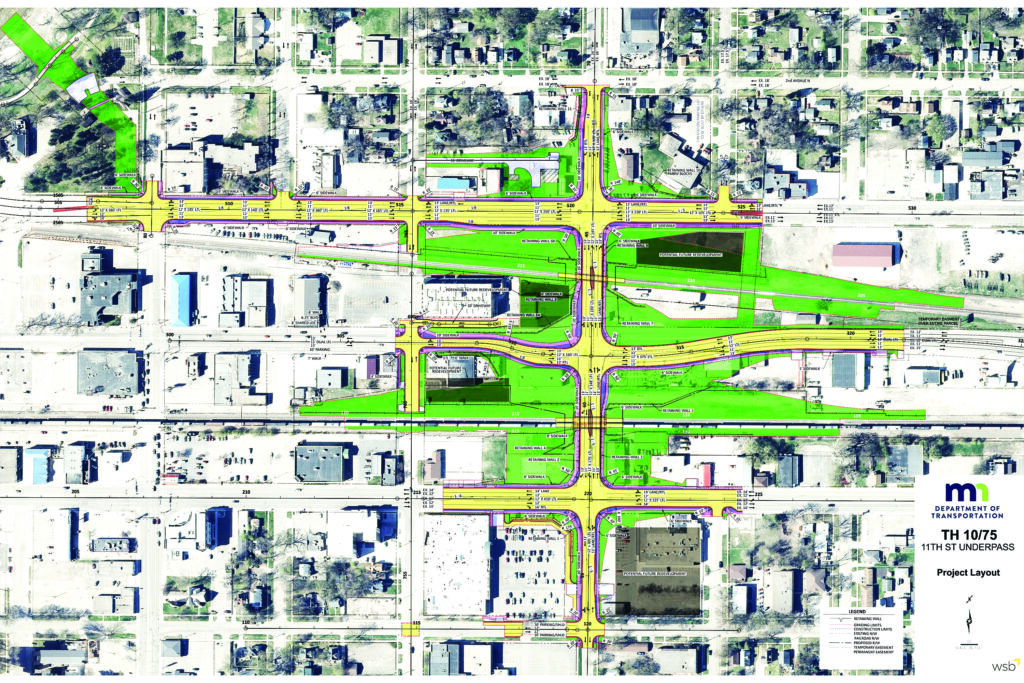

This map by the Minnesota Department of Transportation highlights the areas to be affected during the two-year construction period on 11th Street and Main, Center and First Avenues.

Nancy Edmonds Hanson

The largest infrastructure construction project in Moorhead’s history has already begun after months of study to minimize the risks associated with an undertaking the size of the gargantuan 11th Street double underpass.

At an estimated cost (so far) of $117 million, the two deep dips to be dug between Main and First Avenue North represent the city’s most ambitious project to date. By the end of 2026, drivers moving along 11th Street will be able to travel unimpeded below two overhead bridges carrying BNSF locomotives and long lines of boxcars. With some 70 trains crossing through the heart of the city and delaying cross traffic for five hours a day right now – predicted to rise to seven hours in 2045 – the improvements will help remedy the rail barrier that has bisected Moorhead for some 150 years.

Unlike the 20-21st Streets underpass complex completed in 2022, the downtown project is in the hands of the Minnesota Department of Transportation. (The earlier project was managed by the city.) Given the fresh insights that emerged from the east-side project, MnDOT project manager Justin Knopf says an intense, unusual collaborative process has been employed this time to minimize the risks inherent in such a large and complicated project.

That novel approach is called CMGC, or “construction manager general contractor.” After weighing proposals by a number of candidates, MnDOT chose Ames Construction to fill that role, supplementing and amending the design created by its engineers with an eye to construction methods and pricing. Ames personnel have helped the department make informed decisions on design and staging based on their firsthand expertise – in this case, honed by Ames’ recent experience with the struggles to cope with the area’s difficult clay soil, the legacy of ancient Lake Agassiz. This is only the eighth time the state highway department has turned to this approach.

“This project has to balance the interests of all parties, including the city and the railroad, while operating on tight time lines,” Knopf explains. Cost, too, was a factor in those decisions.

The challenges are complex. The 800-foot stretch of 11th Street will encompass not one, but two excavations, one beneath the future bridge carrying BNSF’s KO line, the other the Hillsboro line a block north. A curving shoo-fly, or temporary detour track, must be laid just north of each rail line to permit trains to travel east and west while an underpass is carved out and a new ground-level bridge is built above it. During that time, trains will operate closer to Center and First Avenues.

Over this summer, Second Avenue has been torn up and is being rebuilt in the first phase of the project. While the underpass itself doesn’t travel there, water mains and sanitary sewers have been dug up and replaced to accommodate shifting ground- and rainwater away from the future digs on 11th Street. At the same time, the city is resurfacing the roadway, something that has been on the city’s to-do list for several years. The work is expected to be complete by freeze-up in early November. Much of the cost is covered by the same appropriations that are funding the nearby underpass.

Knopf says that all of the buildings along the route that will need to be demolished or moved have been acquired by MnDOT. What remains, he says, are temporary and permanent easements along First Avenue to expedite construction by giving the contractor elbow room around the area.

Next on the list of critical decisions will be issuing a contract to build the project. Knopf notes that while Ames was chosen for the advisory role of CMGC, that doesn’t guarantee success when bids are opened in January. “While it’s highly likely, they’re not for sure. Ames and an unrelated contractor will both cost out the work,” the manager says. “If we don’t feel Ames’ estimate is fair and reasonable, we can still open it up for public bidding.”

Construction will be timed out over the next three years. Knopf says alternatives have been considered to make that lengthy period more bearable for those who live in the area, including residents of the recently renovated Union Storage condominiums.

At issue are noise and, especially, vibrations that will be caused by the process of sinking steel pilings 100 feet deep. That’s necessary because of the unstable lake-bottom clay on which Moorhead is built; Knopf half-jokingly compares its texture to peanut butter. The pilings, as long as a 10-story building is tall, can be sunk by drilling with giant augurs or hammered into the ground. The former method is quieter but far more expensive, labor-intensive and slow. On the other hand, hammering the piles causes more severe vibrations – a potential threat to the significant historic structures in the area, including Union Storage, the Armory Event Center and the Fairmont Creamery a few blocks west. A combination of both methods will be employed to balance safety with efficiency and cost.

The buildings’ conditions have been surveyed, Knopf explains, and monitors will be stationed to measure vibration. “If they go off, the contractor must stop and reevaluate the situation,” he assures neighbors. Other steps have been taken to sidestep potential pitfalls, like the collapse of a retaining wall on the 20-21st underpass, including grading at a less severe angle.

While the Moorhead project is not MnDOT’s largest, Knopf acknowledges it may hold that rank among other undertakings outside the five-county Twin Cities metro. “It’s a big one for sure,” he observes. “It’s very unique for MnDOT. I think you could extend that nationwide. There aren’t a lot of projects like this, adding two underpasses downtown with several historic buildings around them.

“Look at it this way. MnDOT’s annual budget for road repair ranges from $40 to $75 million. That’s for all of our roads statewide. So to have this type of project going on in one small area … that’s what I would call major.”