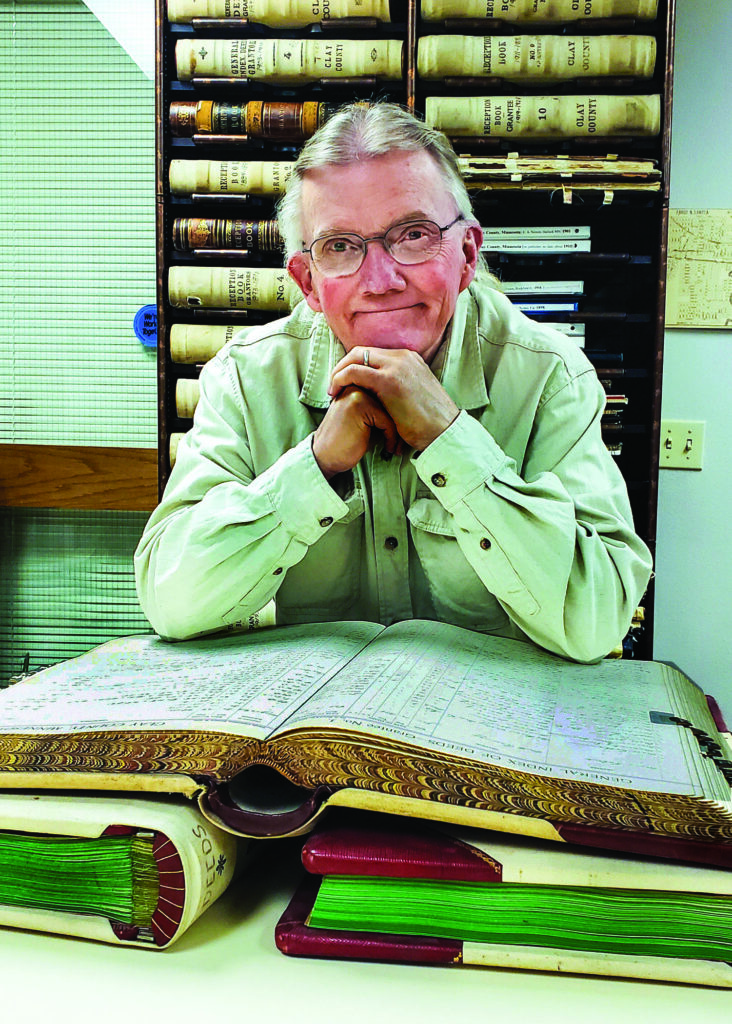

Mark Peihl has is considered Clay County’s foremost historian after more than 35 years maintaining the HCSCC’s vast document collection. (Photos/Russ Hanson.)

Nancy Edmonds Hanson

Mark Peihl is a sort of visionary in reverse: He can see, not into Moorhead and Clay County’s future, but into their past.

For the past 35 years, the soft-spoken historian has manned the archives of the Historical and Cultural Society of Clay County. During that time, he has amassed an unrivaled mental file of facts and fanciful tales of settlement along the banks of the Red – a dramatic tale, full of triumphant highs and murky lows, cataloged and explained to understand the foundation for the region’s future.

That “photographic memory” allusion isn’t accidental. Mark got his foot in the door of the Clay County Historical Society, HCSCC’s predecessor, by sorting and labeling the society’s enviable collection of glass negatives by two pioneer photographers.

Mark had graduated from the University of North Dakota in 1978 with a degree in history, a pursuit that had fascinated him since he spent stifling summer afternoons digging through photos and memorabilia in the attic of his family home in Hunter, North Dakota. But no jobs in his chosen field awaited him. Instead, he spent the next seven years with the Rochester Armored Car Company as a guard and driver, working among “a lot of fellow bachelor’s degree refugees,” he confides.

His portal to the past opened in 1985 when he signed up as a volunteer with the Clay County history group, then housed in the now-long-gone Great Northern Railroad Depot in downtown Moorhead. He spent hours going sorting through its rather chaotic collection of photographic negatives recorded on glass plates. The society’s enormous collection awaited someone to document it – to clean the negatives, transcribe notes on the envelopes in which they were stored, make contact prints and build an index of their historic images. He worked with plates donated by O.E. Flaten, who operated a studio in Moorhead from 1879 to 1929, and S.P. Wang, the Hawley photographer who had been active from 1893 into the 1950s. The Flaten collection of 800 images focused on highlights of the city of Moorhead’s past; the rest of his estimated 140,000 negatives had been recycled for their silver content. The Wang donation was far more extensive, including more than 13,000 images, most lacking identification of the families and individuals who posed.

Mark’s collegiate history studies hadn’t prepared him, he says, for the hands-on work of building an archive – identifying and cataloging the photos or the rest of the society’s rather haphazard accumulation of journals, books, publications and private papers, which were spread from one end of the depot-museum to the other. “It wasn’t entirely intuitive,” he observes with characteristic understatement.

He pored through how-to books on documentation and conservation, archival theory and practice. Those practices have been a moving target throughout his tenure, as evolving technologies have changed the demands of keeping the collection safe and accessible into the future. He continues to hone his knowledge; today he is regarded as one of the foremost experts on archival preservation in Minnesota.

The avid volunteer was added to the modest CCHS payroll in 1986, at a moment when the conversation began to focus on its future rather than the past. The community move was afoot to build a permanent home for the Hjemkomst ship, Robert Asp’s replica of the 9th century Gokstad Viking vessel.

The new Heritage Hjemkomst Interpretive Center, which opened in 1986, included quarters for the CCHS and its three-person staff, including collections manager Pam Burkhart and office manager Margaret Ristvedt. They handled the move themselves, “one piece at a time,” he remembers. “My old Chevy van played a big part. All those drawers and drawers of glass plate negatives ….”

The historical group’s plans evolved in their new home. The team created a long series of exhibits designed to bring people in the door of the society’s new galleries, starting with a sampler of Scandinavian artifacts from the 1930s. Over time, the once-per-quarter exhibits stretched out. “But that plan was absolutely nuts, given our tiny staff,” he concedes. “Now, with three times as many people, each one is displayed for two years.” The current exhibit, “Ihdago Manipi,” explores the dramatic transformation that occurred in the early years of Clay County, from the Dakota, Ojibwe and Metis cultures through the arrival of railroads and immigrant families, the dispossession of indigenous people, an ecological revolution, and the construction of modern American life. It continues through the end of 2023.

Over his career, Mark’s role has shifted from mostly behind the scenes to becoming one of the most familiar public faces of Clay County history. “The vast majority of my time is taken up with providing content for exhibits, writing for publications, and giving programs these days,” he says. “I wish I had more time to spend with the archived, but I do love both aspects of the job.” Along with his articles in the HCSCC newsletter and other publications, he has spoken to everyone from Rotary and Kiwanis clubs to church and homemakers groups to school kids, touring visitors, and the society’s own lecture series.

That’s where he made his first presentation some 30 years ago on the Stockwood Fill, the disastrous railroad project of the 1910s near Glyndon. “We started in the little theater on the fourth floor,” he says. (Unlike most structures, the Hjemkomst’s floors are numbered from the ground level down.) “We were amazed at the turnout! So many tried to cram into that small space that we had to move upstairs to the auditorium. I’ve been talking about Stockwood ever since.”

The county’s history has offered rich material for other presentations, too, among them “Welcome to Beerhead,” the steamboat industry, pioneer pilot Florence Klingensmith, the F-M Electrical Streetcar Company, the prisoner-of-war camps in Moorhead, and – of course – the Flaten-Wang photo collection.

Meanwhile, the archive he manages draws a steady stream of inquiries. Some researchers dig into the past for books and journal publications, like author Keith O’Brien, whose book on Klingensmith and four other female pilots became a best-seller, and Brian Cole, who is writing a history of Moorhead High School. Others track their families’ genealogy and other points of curiosity.

“These collections are a valuable resource, not only for our community, but for historians all over the country and even the world,” he muses. “And maintaining them in accessible through evolving technology is going to remain our major challenge.

“The ways that we collecting and preserve materials has changed greatly over time.” For example, those photographs. They are currently scanned and saved as three different types of digital files, searchable online and stored in three different locations. “We have to continue recopying them and resaving them as formats are introduced and old ones die.”

After 35 years immersed in the area’s past, Mark takes a few minutes to look to the future. His desk is surrounded by file cabinets “jam-packed with every bit of my research files.” He has published countless pieces on innumerable aspects of the region’s history, and continues to share his knowledge with whoever mirrors his interest in how the region reached the point where it stands today – his life’s work.

“There’s nothing unique about me and my stories,” he comments – modestly, of course. “The HCSCC has excellent historians coming along – Markus Krueger, Lisa Vedaa, Emily Kulzer and all the others. We have continuity here … and there will be lots of young people following us in years to come. They’ll do a wonderful job telling these stories in their own way.”